Germany’s Political Earthquake: The Rise of BSW, the AfD, and the Fracturing of the Left

How economic despair, cultural anxiety, and failed centrism are reshaping Europe’s largest democracy

A Nation Divided

Germany’s political landscape is undergoing a seismic shift. The once-stable centrist consensus—anchored by the SPD and CDU—is crumbling, replaced by a polarized contest between Sahra Wagenknecht’s new left-wing Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht (BSW) and the far-right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD). This fragmentation is unearthing deeper fractures: a welfare state in retreat, globalization’s affected demanding redress, and a public disillusioned by decades of neoliberal reforms and identity politics.

While the AfD dominates headlines as Germany’s second-largest party, BSW represents a quieter rebellion—a bid to revive class politics in an era of culture wars. But can either movement heal Germany’s divides?

The Making of a Maverick—Sarah Wagenknecht and the Birth of BSW

From East German Socialist to Left-Wing Firebrand

Sarah Wagenknecht’s career mirrors Germany’s own ideological journey. A former member of East Germany’s Socialist Unity Party (SED), she transitioned to the post-reunification PDS and later co-led Die Linke, Germany’s flagship leftist party. Known for her Marxist critiques of capitalism and razor-sharp rhetoric, Wagenknecht became a polarizing figure—championing wealth redistribution and pacifism while clashing with progressives over immigration and identity politics.

The SPD’s Betrayal and Die Linke’s Unraveling

To understand BSW’s rise, we must revisit the SPD’s Faustian bargain with neoliberalism. Under Chancellor Gerhard Schröder (1998–2005), the SPD abandoned its working-class roots, embracing deregulation and austerity through Agenda 2010 and Hartz IV reforms. These policies gutted unemployment benefits, normalized precarious “mini-jobs,” and legitimized media narratives vilifying the poor as “lazy.” The result? A hemorrhage of SPD voters to Die Linke—a party born in 2007 from the merger of East Germany’s PDS and the ex-SPD members’ WASG (Labour and Social Justice Party).

But Die Linke, too, faltered. By the 2020s, internal factions split between liberal-left activists (prioritizing gender, climate, and Ukraine support) and Wagenknecht’s class-first materialists (demanding economic justice and peace with Russia). When Die Linke backed unlimited military aid to Ukraine, Wagenknecht remarked how Die Linke had become a party of war, and not solidarity. Her exit to form BSW in 2024 culminated decades of disillusionment.

Why BSW?

BSW pledges to refocus the left on material concerns: rising inequality, deindustrialization, and stop Germany’s “Zeitenwende” militarization. Its platform mixes old-school social welfare-state policies (nationalizing key industries, taxing the rich) with populist skepticism of NATO, Ukraine aid, and mass migration.

The Paradox of BSW

BSW’s gamble is that economic justice can trump cultural divides. Yet its stance on immigration and refusal to “pick sides” in the Ukraine war has drawn accusations of flirting with right-wing narratives. Even though the BSW is staunchly pro-peace. Can it unite disillusioned SPD voters and disaffected AfD supporters—or will it fracture the left further?

The AfD’s Metamorphosis—From Neoliberalism to Nationalism

A Party Born of Austerity

The AfD began in 2013 as a protest against Eurozone bailouts, attracting fiscally conservative academics and CDU defectors. But the 2015 refugee crisis turbocharged its shift toward ethno-nationalism, transforming it into a vehicle for anti-immigrant rage, anti-elite resentment, and nostalgia for a mythic German past.

The AfD Playbook

Cultural Grievance: Framing immigration as an existential threat to “German identity.”

Economic Sleight of Hand: Promoting neoliberal policies (deregulation, tax cuts) while posing as a champion of the “little man.”

Anti-System Populism: Positioning itself as the lone defender of free speech against “woke” censorship.

Anomie in Action

As Émile Durkheim warned, rapid social change breeds disorientation—and extremism. The AfD thrives in Germany’s post-reunification “anomie,” where deindustrialization, wage stagnation, and cultural dislocation have eroded trust in institutions. Its base isn’t just the economically desperate but those fearing decline—a potent mix of insecurity and resentment.

AfD and NATO: Wolves in Sheep’s Clothing

Despite posturing as “anti-Ukraine war,” the AfD is no peacenik. While it criticizes Germany’s military aid to Ukraine and calls for dialogue with Russia, the party explicitly supports NATO and even advocates expanding Germany’s military budget to 5%. Its 2023 platform vows to “strengthen NATO as a defensive alliance” while opposing EU defense integration—a nationalist twist, not an anti-imperialist stance.

Clash of Counterweights—BSW vs. AfD

Two Crises, Two Visions

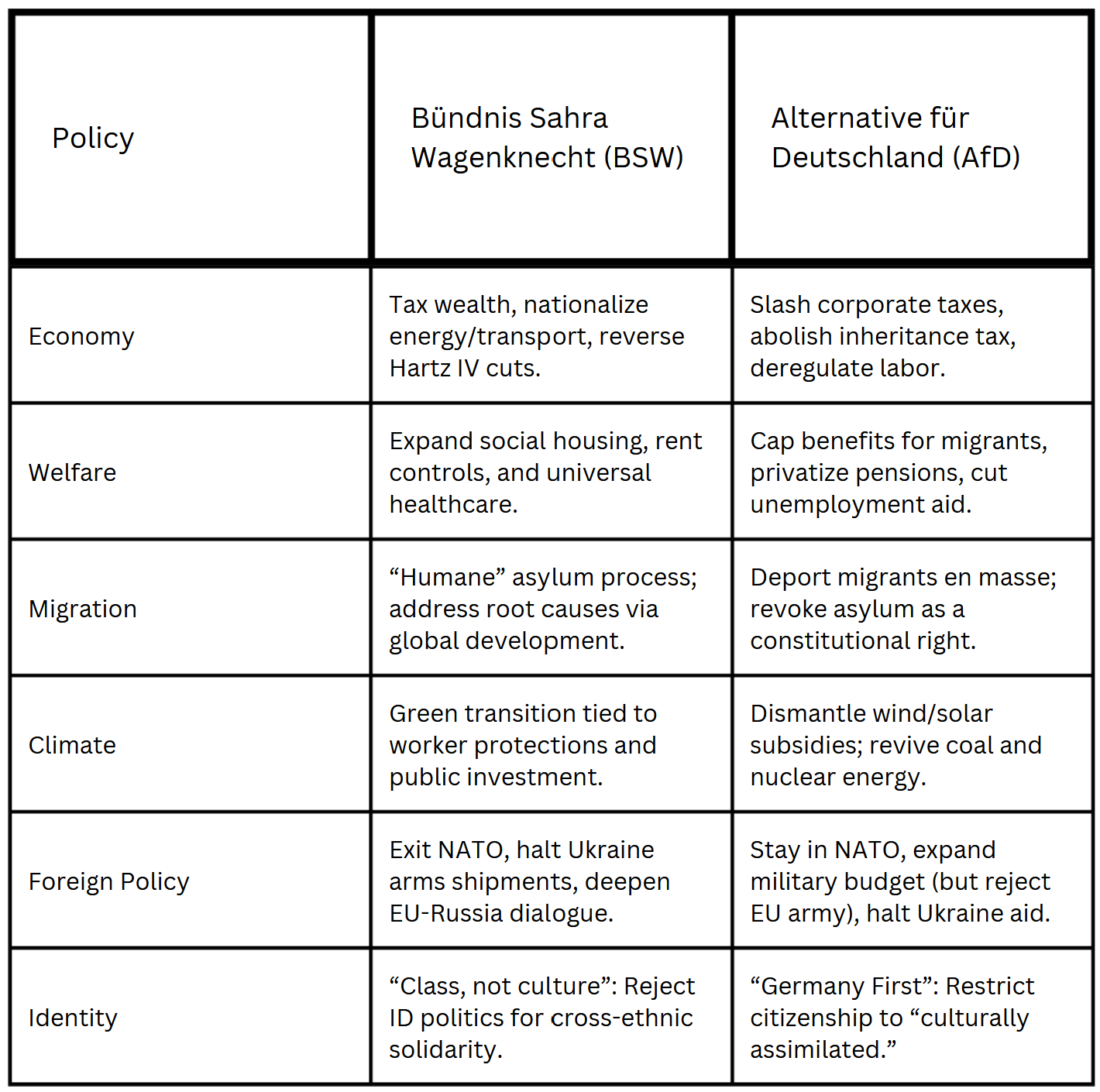

BSW and the AfD both channel voter rage at Germany’s political establishment—but their platforms could not be more opposed. One seeks to resurrect class solidarity; the other, ethnic nationalism. Below, a breakdown of their stark differences:

BSW’s Gambit: The Return of Class Politics

Wagenknecht’s party frames inequality as systemic—a product of neoliberal capitalism and corporate greed. Its solutions are unapologetically social: tax the rich, renationalize privatized industries, and rebuild the welfare state. BSW’s anti-NATO stance, rooted in Cold War-era pacifism, aims to appeal to voters weary of Germany’s militarized “Zeitenwende.”

AfD’s Illusion: Nationalism as Neoliberalism

The AfD poses as a defender of “ordinary Germans” but promotes policies that would deepen inequality. Its “Germany First” rhetoric masks a hyper-capitalist agenda: slashing taxes for the wealthy, gutting worker protections, and privatizing public services. Despite claiming to oppose war, the AfD staunchly supports NATO (calling it “essential to German security”) while trying to stop funding to Ukraine—a contradiction that reveals its opportunism, not pacifism.

Shared Ground?

Both parties exploit distrust in media and elites, but their voter bases diverge:

BSW: Targets East German workers, disillusioned SPD voters, and anti-war leftists.

AfD: Appeals to small-business owners, staunch conservatives, and those with anti-immigrant sentiments.

The irony? While BSW and AfD voters both feel “left behind,” their movements are mutually exclusive—one blames capitalism, the other scapegoats migrants.

Why This Divide Matters

Germany’s political realignment isn’t just about left vs. right—it’s a battle over what constitutes justice. BSW argues poverty stems from exploitation; the AfD claims it’s caused by “outsiders” draining resources. The CDU, meanwhile, offers reheated neoliberalism with a xenophobic garnish.

As Bertolt Brecht warned in The Threepenny Opera:

“Food is the first thing. Morals follow on.”

Brecht’s maxim cuts to the heart of Germany’s crisis: when material needs go unmet, morality fractures. BSW and AfD represent two paths from this rupture—solidarity or scapegoating. The question is which vision voters will stomach.

The CDU’s Rightward Lurch—Chasing the AfD’s Tail

From Merkel’s Center to Merz’s Culture Wars

The CDU, once Germany’s natural party of government, is in crisis. After Angela Merkel’s centrist reign, new leader Friedrich Merz has pivoted hard right to recapture voters flirting with the AfD. The strategy? Mimic AfD talking points:

Anti-Immigrant Rhetoric: Merz warns of “parallel societies” and demands faster deportations and an end to dual citizenship.

Welfare Bashing: Labeling unemployment benefits “an invitation to idleness.”

Climate Backlash: Slamming the Greens’ energy policies as “economic suicide.”

A Dangerous Game

The CDU’s shift risks normalizing far-right narratives. By echoing AfD slogans, Merz legitimizes xenophobia while offering no solutions to inequality. Polls suggest the tactic is working—the CDU leads nationally at 30%—but at what cost?

As Bertolt Brecht wrote in The Solution during the 1953 East German uprising:

“Would it not be easier / In that case for the government / To dissolve the people / And elect another?”

Brecht’s sardonic question mirrors today’s establishment conundrum: rather than address voter despair; the CDU seeks to “dissolve” dissent by becoming the AfD-lite.

Weimar Shadows—Can Germany Avoid Democratic Collapse?

Echoes of the 1930s?

Germany isn’t Weimar—yet. But the parallels are unsettling: economic inequality at pre-WWII levels, institutions struggling to contain extremism, and a seemingly centrist elite discredited by austerity and war. The AfD’s normalization (now polling at 20%) and CDU’s rightward lurch suggest democracy erodes from within.

Rebuilding Solidarity—A Durkheimian Prescription

Sociologist Émile Durkheim argued that social cohesion requires shared values and robust safety nets. For Germany, this means:

Economic Renewal: Invest in housing, healthcare, and reindustrialization to restore faith in democratic processes.

Migration Realism: To ease cultural tensions, pair humanitarian asylum with integration programs. Create a regional migration and asylum policy that is implemented correctly.

Democratic Reinvention: Empower unions and local councils to bridge the gap between elites and citizens.

Conclusion: Bridging the Divide

Germany stands at a crossroads. The AfD offers scapegoats and nostalgia; BSW, a fading dream of solidarity. The SPD and CDU, meanwhile, cling to a broken status quo.

Yet history offers hope. Post-war Germany rebuilt itself through social democracy and inclusivity. Today’s crises demand similar ambition—not hollow pragmatism, but a politics that marries economic justice with cultural belonging. The alternative is unthinkable: a fractured nation, forever teetering on the edge.

Recommended Resources

For readers eager to dive deeper into Germany’s political upheaval, neoliberalism, and the clash between left and right populism:

Books

Philip Manow, The Political Economy of Populism (2023)

Explores how economic inequality fuels populist movements, with case studies on Germany’s AfD and Die Linke.

Wolfgang Streeck, How Will Capitalism End? (2016)

A Marxist critique of neoliberalism’s erosion of democracy, essential for understanding the SPD’s decline.

Sheri Berman, Democracy and Dictatorship in Europe (2019)

Traces Germany’s post-war democratic stability and its current fragility through a historical lens.

Jan-Werner Müller, What Is Populism? (2016)

A concise primer on populism’s mechanics, useful for dissecting BSW and AfD’s rhetoric.

Videos

Garland Nixon - THE WIT AND WISDOM OF MARK SLEBODA EP 8 - EU COMING UNGLUED - UKRAINE FRONT LINES (2025)

While not explicitly about Germany, this YouTube episode touches upon European politics and its left-right divide in a geopolitical context.

Die WELTWOCHE - «Der Krieg ist für die Ukraine verloren»: Weltwoche-Gespräch mit Viktor Orbán und Gerhard Schröder (2024)

Unfortunately, this is in the German language but reflects the neoliberalization of the SPD

The Duran - Germany Deindustrialising & Subordinated - Sevim Dağdelen, Alexander Mercouris & Glenn Diesen (2025)

Fascinating discussion with a BSW member about their foreign policy stance.

Final Note

These resources offer lenses to dissect Germany’s crisis—from neoliberal economics to the moral decay Brecht warned of. For those short on time, start with Philip Manow’s works.

Let me know if you’d like links or additional suggestions!

Support Independent Analysis

If you found this deep dive into Germany’s political crisis valuable, consider supporting my work:

Subscribe to this Substack for more long-form analysis of European politics and populism.

Share this article with friends, colleagues, or social media—debate thrives when ideas circulate.

Democracies fray when scrutiny fades. By subscribing or sharing, you help sustain independent journalism that cuts through noise and dogma.

Contact:

Twitter: @Nen_senb

Substack Comments: I look forward to hearing your thoughts!

Stay curious,

Nel

A great summarized article about the two big political parties written in a simple tone which helps a person like me who is not so familiar with German politics to understand the same.

Great Job! Will look forward your future articles.

0. Thank you very much for the excellent introduction. Specifically, I like the itemized presentation about the contrast in the policy differences between the two party platforms. I have learned something today.

1. BSW needs a starting point, a little bit of real power in local/state politics. Maybe BSW should focus on one German State in the east before really trying to go national. Tactically I think BSW is likely to lose out because its policies are more moderate and more humane. AfD is more likely to win out in the short term. This is similar to the American Conservative: There is the DJT kind of MAGA crowd, very much like AfD. Nationalistic, patriotic, but short-sighted in policy designs. So far it seems DJT does not really have a coherent vision for anything besides his intention to weed out the deep state. There is also the non-DJT MAGA crowd who are rarely talked about by political analysts. The second group of folks, me included, do not completely agree with DJT policies. I feel the DJT-MAGA is to the right of AfD, while the non-DJT-MAGA is to the right of BSW (I am anti-welfare in general, but I now believe some limited form of social safety net is necessary.)

2. My original concerns about this contrast between AfD and BSW were based on my shallow understanding of post-WW1 Germany. Specifically the Freikorps and the communist-leaning Labor movement (maybe even can be said as Communist Rising as some authors do). Hitler played the nationalism cards very well: he reminded the German people about the humiliation and suffering imposed on them by the Western countries and channeled anger onto the minorities, especially Jews. Once the hatred is consolidated, as is now, the political elites will play the undissipated hatred in the direction they want after "the mob" releases the anger on the designated victims and feels a kind of twisted victory. Given that AfD has a critical weakness in wanting to stay inside NATO while increasing the defense budget, that manipulation is predictable after the "immigration issue" fades out. I am all for strong defense spending but for a truly independent Germany, or any nation for that matter, surely not for a Germany under the yoke of EU or NATO. In this aspect, AfD are misled nationalists. I have sympathy for them as they are the same as the bulk of the DJT-MAGA crowd: they know they have been cheated, exploited, misled, and they are angry. However, they are not deep-thinkers or erudite. Anyone able to consolidate their anger and direct that anger onto the designated victims will get their support. After WW1, the best victims were the Jews. Right now, they are illegal immigrants. And it is easier to hate illegal immigrants after they have committed some violent crimes. If BSW cannot get out of the shadow of the German Communists, it will definitely suffer. Nationalism needs mostly emotion and bravery, but proper socialism needs a lot of brains and high morality.

3. I forget the name of the writer who said that now is the time for the intellectuals and the labor to unite. I think the original writer said so in the context of American politics. This juncture is similar to China right after the Republic was established after armed revolutions. Given that China had no cultural basis for democracy and lacked all kinds of necessary basis for democracy, the government, the people, and the nation were all a big mess. Traditional culture and philosophies were abandoned, much like German people today know that the old way is not working, but there is no clear sign as to which policy platform, or ism, was the best. Whoever has the most money, the rifle butts, and the charisma in popular movement will win. Intellectuals typically follow the wealth, the establishment, and the government for a living, and sometimes a career. In most of the more industrialized nations, the wealthy and the political elites are corrupt from the eyes of the little guys while the general public wants changes but does not know what or how to change. Red neck policies tend to be short-sighted and will backfire quickly. One example is the MAGA crowd want to protect their almost nonexistent inheritance but only become the cover for the super-rich. A true nationalist actually should be a socialist as well. How much one can afford to socialize depends on how much wealth he has.

4. The intellectuals and the white-collar professionals want to think of themselves as being part of the elites or the upper class. The truth is computer automation has destroyed many middle-class jobs and more of the same is coming in the form of AI. A little bit earlier, skilled labors had been hurt since robotics entered manufacturing. Instead of sitting pretty at the higher end of the Gaussian Distribution, the white-collar professionals and the intellectuals are now falling into the center of the M-formed society. That M is not only appropriate for Japan in 2006 but also true for many well-developed economies now. There is little growth, only financial engineering and stock market manipulations. At the same time, resource depletion will make all forms of social welfare an ideal too far.

5. The intellectuals have to shoulder the responsibility of clarifying to the general public how the public have been fooled, and what tricks and venues are still being used to mislead the public. However, given the financial oligarchs and the political elites remain tightly coupled together, and most of the military establishment are corrupt as well, it seems only large social unrest can shake the status quo. Otherwise, AI, robotics, and Skynet will protect the upper class and civilians will never be able to challenge them. Kind of like the Medieval time and 1984 but more horrifying.